As part of our Citizens Assembly submission we gathered the real stories of real women who had been affected by the 8th Amendment. Now, as we approach the referendum to remove the 8th from our constitution and allow compassionate care in Ireland, we are reproducing some of the stories, with permission. We want to thank those who submitted with us. Please share widely.

On the 28th of May, 2015 I travelled from Dublin to the Southern Manchester Clinic for a surgical abortion. It was a sunny day in Manchester, but the 4:30am Dublin wind was ice cold against my legging-clad legs. Leggings were a must. Easy to travel in, easy on my abdomen that had surprisingly failed to show any visible difference, easy to curl up in on my long journey home. I do not mention these details because they hold significance in and of themselves. I mention them because I want you to understand that, although my decision to have an abortion was not, for me, a difficult one, it is a decision that took deep consideration, much research and careful planning. It is an event that has shaped me as an individual, as a woman, and as an Irish citizen.

Although I do not feel as though I should have to justify my unplanned pregnancy to anyone, I am writing this piece in the hope that you, the reader, will fully understand my reason for doing so. So here it goes. When I got pregnant I was not using hormonal contraception methods (the pill, the bar, an IUD) as I had tried these before and experienced problematic side effects. Therefore we were using condoms, ironically the most effective form of contraception (apart from abstinence of course), however in this particular instance, we were the 1% and realised it too late. I hastily calculated the dates and concluded that it would be ok; besides, I had taken the morning after pill once before and had suffered debilitating cramps for over a month afterwards. At the time, with exams and essay season right around the corner, chancing it seemed the better of the two options.

It is so important to make clear that I was incredibly privileged in almost every aspect of my unplanned pregnancy. I was privileged in that I did not become pregnant through the traumatic circumstances of rape or abuse. I was privileged in that I had someone I knew would support my decision and travel with me, unlike the thousands who must travel alone out of fear of being shunned by friends or family. I was privileged in that I had the right to travel, which asylum seekers across this country do not (and are not entitled to a special visa or an abortion, as demonstrated by the Y case). I was privileged in that I was over 18 and not in the care of the state, unlike many vulnerable people who would be denied the right to travel for an abortion on constitutional grounds, as the state, as the primary carer of those institutionalized, cannot deny the right to life of the unborn (despite the right of every other Irish citizen to travel for this procedure). I was privileged in that I was aware of the risk I had taken, and could act immediately once I missed my period, unlike other women I know who have continued to get false periods caused by hormonal contraception implants (yes, that’s a thing) and did not realise they were pregnant until they visited the doctor with a vomiting bug, only to discover it was in fact morning sickness. I was privileged in that my family are in a position whereby they can support me, paying my college fees and basic maintenance, so that I did not have to source money, I could use the wages I had saved up. I was privileged in that I do not fulfil the duty of care to a child, an elderly relative or a sick family member, which so many women in this country take on, and is a huge barrier to travelling for an abortion. I was privileged in that I was in full health, and both physically and mentally capable of the journey to England. I was privileged in that I could travel for medical treatment from a professional under medical supervision in a sterile environment, as opposed to being forced through circumstance to import illegal pills, not knowing whether they’re delayed in the post or stopped at customs, consuming them alone without a national abortion aftercare helpline or a doctor who can help without risking a jail term. I was privileged in that I have only ever used hangers for clothes. I was privileged in that I was not suicidal. I was privileged in that this was just an accidental, unplanned pregnancy, and not a fatal foetal abnormality; forcing so many to make impossible the choice between waiting for the inevitable miscarriage, smiling meekly at each person beaming at your bump, asking whether it’s a boy or a girl, knowing your chances of having a child are slim to none, or travelling abroad, with the remains posted via DHL, or in a shoebox in the car on the ferry home.

Because I could not simply book an appointment with my GP and take an abortion pill within the first 3 weeks of my pregnancy, I had to have a surgical abortion at 10 weeks. Although my family are not overtly religious, the idea of the perfect daughter having tarnished herself and winding up pregnant is much more than the majority of them could comprehend, and I could not think of a reason my parents would believe for suddenly going away on an overnight trip when I had exams in less than 3 weeks. Besides, flights are hundreds unless you’re booking them at least a month in advance, especially around Easter. So I decided to wait, to write essays pregnant, to sit my exams pregnant, to down pints of water and attempt deep breathing exercises in an effort to quell the morning sickness that hit me on the journey to my exam every morning without fail, turn 21 pregnant, wait for my boyfriend to finish his exams so that we could travel together, and finally flee the country quite literally like criminals on a 6am Ryanair flight to Manchester.

A Muslim taxi driver collected us from the airport and brought us to the clinic, a free service for Irish women to compensate for the expense and extra travel time. Outside the large redbrick building, we saw an elderly woman wearing a long purple coat, standing slightly hunched and clutching what we later realised were rosary beads. Our driver informed us that nuns took shifts outside the clinic each day, maintaining a constant vigil. Ironically, as our driver said this, his manager radioed in to give his permission for the driver to go on a break and answer the call to prayer. I found it funny how Islam is so often depicted as a highly conservative, sexist and strict religion, bound up with stories of female submissiveness and harsh penalties for female ‘sexual crimes’ such as adultery; yet here we were, guided to an abortion clinic by a friendly, supportive and non-judgemental Muslim man, and tutted at by a conservative, judgemental Christian woman.

It was only 9:30am yet I was already exhausted. For privacy reasons, partners, friends and relatives had to wait at reception. My boyfriend took my hands, looked into my eyes and told me everything would be ok. And I knew it would be, because I was finally being treated by a medical professional, for only the second time in my pregnancy. Before booking my abortion I had attended a crisis pregnancy counselling session, provided by the IFPA (Irish Family Planning Agency), where a trained counsellor discussed each of my options (parenting, adoption and abortion) and insured I knew the risks of each pathway before I made my decision. Although it was up to me to book the procedure myself (basing my choice solely on message boards and the reliability of a clinic’s website, which we all know is risky in the digital age), the IFPA could assure me that my chosen clinic was a reputable one. However, had I not researched clinics beforehand, they would not have been allowed to provide me with a list, and so there would have been the risk that I could have been scammed by a backstreet abortion provider, risking my health. I also attended the college doctor, who was totally bewildered as I gave her as much information on my family’s health history as possible, trying to gauge whether having an abortion would be dangerous for me. Again her hands were tied, and she could only tell me that based on my physical and mental health and family history, I appeared “fit, should there be some kind of surgery you may need in the future” and that there “are various types of counselling available, you know the IFPA?” I was not entitled to a scan, or even an honest medical assessment and discussion of my condition.

The first nurse went through my personal details and medical history, outlining the procedure and all possible risks, and ensured I was psychologically fit to understand, consent to and undergo an abortion. She informed me of post-abortion counselling in Ireland, and gave me the UK post-abortion helpline number, as no such service exists at home. Things took a confusing turn when I met with the second nurse, who, on performing an ultrasound, could not find any sign of foetal viability. She asked how many weeks along I was and, on saying 10, she frowned a little and noted ‘size: 6 weeks’ on my form. On consulting another nurse, and then another, she concluded that I had miscarried at least 3 weeks earlier. Abortion or not, lying on a paper-covered bed in a foreign country with your pelvis lathered in lubricant, vulnerable and alone, is not the way to find out that your 21 year old body, in its reproductive prime, has failed on its first pregnancy. I was not sad that the foetus was not viable, as I had never envisioned this pregnancy developing into anything more. I was afraid for my future, for the children I had planned to have in ten years’ time. Was I sick? Did I have an undiagnosed condition? A tumour maybe? Did this mean I was infertile? The nurses were so incredibly kind, fast tracking my file so that I could see the doctor as quickly as possible. I was classed as ‘at risk’, because my body could complete the miscarriage at any time, which could lead to haemorrhaging. Haemorrhaging. The picture of Savita Halappanavar used by RTÉ floated into my mind.

I sat in the waiting room, listening out for my number and colour. For confidentiality reasons, we had all been given purple or yellow cards, each with a different number on them. My boyfriend later told me he thought yellow was for abortion pills, while purple was for surgery, as the yellow card women came and left much more quickly. I was Purple 7. As I looked around the room, I noticed that most of the yellow card holders were older, at least 34. Perhaps that’s where the myth of abortion services being predominantly used by irresponsible 20-somethings come from. Maybe older women have just as many unplanned pregnancies, but have the resources to book an abortion more quickly. (Actually, according to a recent Irish Times article, older women do make up the majority of abortions, and are usually already mothers). Of the 15 of us in waiting the room, I was one of the youngest, apart from the underage girl with her mother. We were black, white, brown, tanned, cream, pink, yellow. Some wore work clothes, others tracksuits, others headscarves. No one cried, no one looked upset, no one even looked pregnant. There is no one story, there is no ‘type’ of woman who gets an abortion. There is only circumstance and necessity.

When it was my turn to meet the doctor, he looked at my file, confused, and left the office for a few minutes to discuss my scan with the nurse. On his return, the procedure was discussed again, and again I was informed of the various risks involved. The doctor asked what I had discussed with my GP after my initial scan, and he shook his head in disbelief when I told him that I had not been entitled to a scan before leaving home, despite contacting my college doctor and the national crisis pregnancy services. He calmly explained to me that I had been miscarrying for at least 3 weeks. I asked whether I could have in fact been treated at home, but he informed me that, under Irish law, doctors could not act until I had actually miscarried. He told me that in fact, although flying was a risk, I had actually taken the safer option, as an unsupervised miscarriage can be extremely dangerous to the woman’s health. I could not believe that, had I been intending to continue with the pregnancy, I would have ended up in Manchester regardless. I still cannot believe that the state will not allow our doctors to give unbiased advice on the safest course of action when faced with a problematic pregnancy or miscarriage, and that, had I not been able to travel, I would have had to go about my daily life, knowing I could begin to haemorrhage at an point, knowing that if the miscarriage completed in my sleep, I may not have noticed the blood until it was too late. Knowing that I could not be treated in Ireland until my life was on the line. That I quite literally could have died sometime over the last three weeks.

Although I have not been negatively psychologically affected by my abortion, this thought continues to haunt me. As I was driven from the clinic back to the airport, where I waited for 9 hours before our 11pm flight home, all I could think of was how I was just a pregnant body to the state, a vessel, an incubator of potential life, not a human being whose life was at risk. It was the longest 9 hours of my life. Unable to afford a hotel and more taxi fares in Manchester, we’d opted to wait it out in the airport and to instead stay in a Dublin airport hotel that night. Most of the time was spent sprawled out on a café table, clutching my abdomen and squirming at the waves of cramps. Every 40 minutes I’d spring from the table and run towards the bathroom with my hand clamped over my mouth, sure that it was more than just nausea this time. I bled and bled and bled while sitting on the cold steel seats. All I wanted was to be at home on the sofa, with a hot water bottle against my tummy, the old reliable basin by my side and a large Penny’s blanket swaddling me, safe and secure like the times when I had been sent home from school as a child years before. After an agonizing 7 hours, we attempted to construct some kind of normalcy and squatted on the Gate 7 waiting area seats, watching House of Cards from the tiny screen of my phone. It wasn’t home, but it was the best we could do.

Once we got back to Dublin, I didn’t sleep at all for fear of accidentally soiling the pure white hotel sheets. We returned to our family homes the following day, both ‘back from a weekend away with the college lads/girls’ to avoid arousing suspicion. None of our friends knew. With an issue as controversial as this, it’s hard to know who you can trust, and how people will react. Day two was worse than the first, as the pain got so bad that I blacked out twice. Once in bed, and once on the bathroom floor of my family home at 4am. Thankfully I came round before anyone found me. The bleeding was heavy and clotted, but I did not have enough credit to ring the UK number I had been given. I should have gone to hospital, but I had no cover story. I risked my health in order to avoid hurting my parents, whose views have been shaped by a Catholic education and conservative rhetoric circulated by many Irish politicians and media sources. In retrospect, my decision to stay at home was ridiculous, but at the time I was paralysed by fear of being rejected by my family.

Thankfully, I am once again in full health. I have not been permanently scarred, either emotionally or physically, by my decision to have an abortion. I have found the courage to tell my sister and a few very close friends, but I doubt I will be confident enough to tell my parents while abortion is still illegal. Nevertheless I have become so impassioned on the issue of repealing the 8th amendment. There are as many reasons for a woman choosing to have an abortion as there are women who have them; there is no one story, and so we cannot maintain or replace the 8th amendment in the hope that the state can foresee all possible circumstances and legislate accordingly, making those who are ‘entitled’ to an abortion go through endless referrals and examinations, for the sole purpose of restricting others. No one uses abortion as a form of contraception. It is not a decision taken lightly, it is not fashionable or a badge of honour. It is simply a choice. It is a choice that every individual should be allowed to make for themselves. We cannot allow highly emotive and individualistic factors such as religion stand in the way of expert medical opinion. We cannot keep exporting our women. We cannot trade the health and wellbeing of those unable to travel for some moral high ground that punishes the most vulnerable in society. Please, please, vote to remove the 8th.

**Although we booked the flights and abortion 6 weeks in advance, which most people do not have the luxury of doing, the entire trip cost over €750, including airport taxis in Dublin, flights, new pyjamas towel etc I could dispose of at the hotel, abortion procedure, airport food during the day and airport hotel in Dublin.

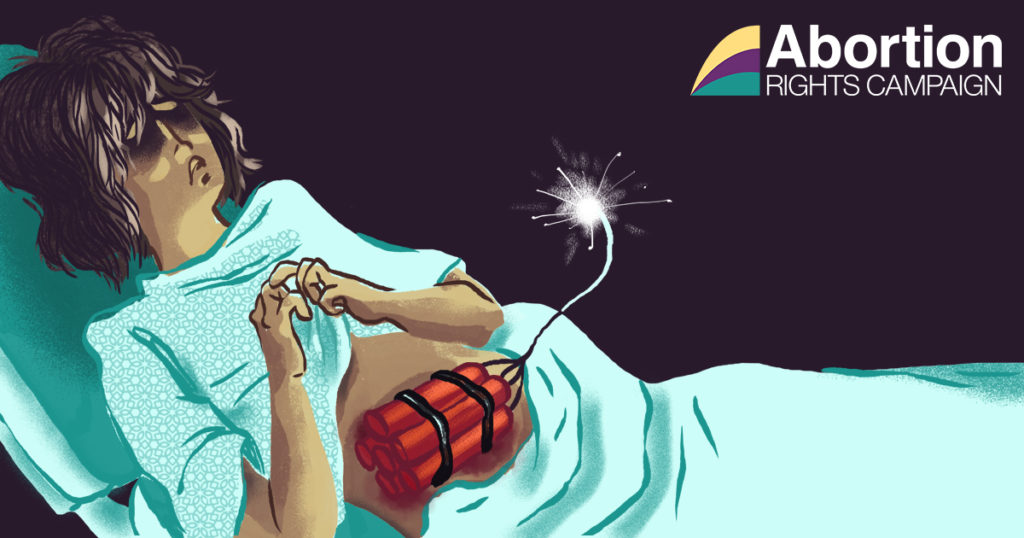

illustration by Mollie Little

This is what the Republicans in the US want our country to return to, a place where a woman has no right to choose to end her pregnancy.

Thank God I never needed an abortion, have three lovely children and the support both emotional and material, but many women do not, and I do not want the choice taken away from anyone.

This is a frightening prospect.

This is really impressive blog post..